By Memuna Forna

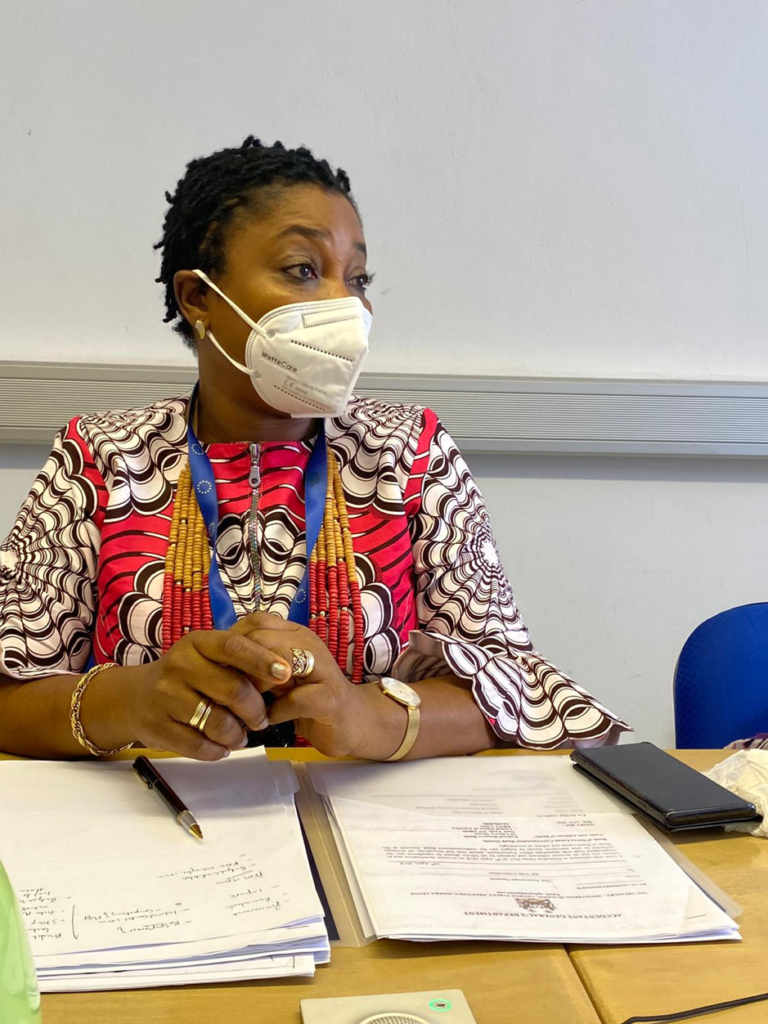

In January 2013 Lara Taylor-Pearce, Sierra Leone’s 2011 appointed Auditor General (AG), was summoned to Parliament to appear before the Public Accounts Committee.

She had caused a nationwide uproar by making the Audit Service’s 2011 annual report publicly available; something her predecessor had never done. She had also redesigned the report to make the findings and recommendations more accessible to a lay audience.

In an hour-long grilling, the 10-man committee demanded to know why.

Point by point, Lara Taylor-Pearce made her position clear. “I will not be intimidated,” she told them. From 2009, the Audit Service Sierra Leone (ASSL) had been given the authority to make their findings public, so she was acting entirely within her mandate, she explained. Then using case histories from around the world, she demonstrated that accountability and transparency were in the public interest and played a key role in improving efficiency and reducing corruption at all levels within the public sector.

It was the start of what proved to be a good and productive relationship with the Public Accounts Committee at that time.

It also provides a revealing insight into Lara Taylor-Pearce’s character. She is meticulous, a stickler for knowing the rules and abiding by them – without fear or favour. “I like things to be done properly,” she states.

These qualities have carried her through some particularly bruising battles. Most notably, the real-time audit of Ebola funds, which exposed massive corruption, led to a major overhauling of the management of the funds and saved many lives.

Most countries have a national external auditing institution to monitor the financial operations and performance of public sector bodies. Ours dates back to the Audit Act of 1962. This established an external audit function to replace the Colonial audit service. For 36 years it existed as a quiet little unit, hidden within the Ministry of Finance, until the Audit Service Act 1998 paved the way for the Audit Service Sierra Leone – an independent institution which reports to Parliament, in line with international best practice.

The 1998 Act ultimately gave way to the Audit Service Act of 2014. This includes sections that elaborate on the functions and powers of audits, terms and conditions of service of ASSL staff and the exemption of ASSL staff from the Public Service Commission.

Lara Taylor-Pearce explains the ASSL’s role by comparing it to corporate governance. “Corporate governance is the cornerstone of any good business,” she says. “It encompasses the processes, practices and policies that a company relies on to make formal decisions and to manage the company. Imagine Sierra Leone as a private company with shareholders, a management team and board. The shareholders are the citizens, the executive are the management team, and the board is Parliament.

“When we audit the MDAs, we are checking that public funds are managed in an effective and efficient manner in compliance with existing laws. Then we report to Parliament with our findings. It is an important part of any country’s governance structure.”

Obviously, Supreme Audit Institutions like ASSL can only accomplish their tasks objectively and effectively if they are independent and protected against outside influence. In Sierra Leone, the independence of the audit office is enshrined in law.

Although the President has the power to appoint the Auditor General, his appointee has to be confirmed by Parliament. To ensure the security of the Auditor General, he or she can only be removed from the post under certain provisions in the constitution. In some countries the AG position has a term limit. In Sierra Leone, the position has security of tenure. Other members of staff are appointed by an advisory board, which is not involved in the day-to-day running of the ASSL.

If there is an Achilles heel to ASSL’s independence, it is that funding comes from the Ministry of Finance. “In jurisdictions that have understood the importance of independent public sector auditing, funding for the audit office is approved directly by parliament, with the budget “ring fenced” by them, ” says Lara Taylor-Pearce.

When she was appointed Deputy AG in 2007, she already had a clear understanding of the challenges ahead, gained from several years providing technical expertise within the Accountant General’s office under a European funded project, with further experience in supporting Public Financial Management in two World Bank funded programmes.

“For the process to work, there are certain essentials,” she explains. One of them, is that the Vote Controllers within the MDAs (the public officer in charge of managing funds – usually the Permanent Secretary) actively engage.

To this end, the ASSL follows a comprehensive multi-step process. Each MDA to be audited receives an engagement letter. This lists the financial and other information required. The process will be further clarified at an introductory meeting between the Vote Controller, senior staff and the ASSL.

“During the fieldwork, the ASSL will examine documents, analyse data, conduct interviews and has the right of access to all information deemed necessary to the task. Any queries arising are usually resolved on the spot,” says the AG. “However, if the answers are not forthcoming, we will follow up with written queries. Outstanding queries are revisited at the exit meeting.

“After this we prepare a report on our findings and recommendations for the Vote Controller. This provides another opportunity for the institution to revert with any queries and their responses. Most times this is enough. What remains unresolved finds its way into the reports that become public.”

“The elephant in the room is procurement. Often it is not done properly, contracts are incorrectly drawn up, or they have over-charged or colluded.” She lists the other issues they see year in and year out, and it’s like another language. Lack of reconciliation, unretired-imprests, taking taxes from the supplier and not paying them to the NRA all feature prominently.

The audit stage of the process is necessarily exhaustive, because when the ASSL submits its report to parliament, it is also made accessible to the public, who are increasingly aware of the power of public scrutiny as a catalyst for improvement.

As John F.S. Muwanga, Uganda’s Auditor General, has said: “Public audit is today being tested as a mechanism for promoting accountability and transparency within government, especially in developing countries. The protests about service delivery are growing in volume, but what is the auditor’s role?”

Lara Taylor-Pearce’s take is that the ASSL’s role is not to detect or investigate corruption, but that their work is relevant to the fight against corruption. She says: “ASSL and ACC share a commitment to ensure accountability in government finances. If the audit service was given the required level of support and tools to do its job – the ACC’s work would be much easier.”

For that to happen, she believes, Parliament needs to take a tougher line with MDAs so that they comply with requests for information, implement recommendations and genuinely engage with the audit process.

Nevertheless, she is aware that the ASSL has made great progress. Under her leadership, it has grown into an organisation with an international reputation for excellence. Today, it employs over 120 highly-skilled technical staff. “We only take the best, from those who apply for our jobs,” she says, “and we actively support continuous professional development.” The success of the ASSL’s human capital development strategy means that its staff are regularly called upon by audit offices in the region to provide professional oversight or staff training.

And while parliament may struggle, at times, to throw its weight behind the work of the ASSL, the same can’t be said of the general public.

When Lara Taylor-Pearce took the decision to make the annual audit reports publicly available, she handed Sierra Leone’s citizens the power of public scrutiny. They have used it to save lives, reverse injustices and prevent misplaced trust. We should continue to ask for answers to the queries raised in the audit reports, but this shouldn’t be the extent of our aims.

The governance culture we really need is one which welcomes effective scrutiny and accountability, as a way for communities and decision-makers to work together on improving public service delivery.

Lara Taylor-Pearce’s vision of a public audit office which is allowed to do its work with the committed support of Parliament is a vitally important step towards achieving that goal.

As Auditor General, she shows us the possibilities of good governance in Sierra Leone. To achieve them, we have to start playing by the rules. All of us, without fear or favour.

Source: OWL Press